Public discussion about suicide is dominated by particular types of narratives. Media outlets tend to focus on celebrities who, despite outward signs of success, are tragically driven to despair. Other news stories tell heartbreaking tales of young people who end their lives after experiencing readily identifiable stressors. This coverage is important, and compassionate media depiction is crucial for public understanding. However, discourse that’s constrained to certain kinds of stories obscures two key points: 1) suicide is really complicated and 2) it can affect anyone. With a trend of rising suicide rates in the United States, we need to expand our conversations and make more room for nuance.

Five years ago, I heard a story about a suicide attempt that broke the typical media mold. It was this powerful NPR Story Corps segment about a man named Kevin Berthia, who was extremely close to jumping off the Golden Gate Bridge. In under three minutes, listeners learn that Berthia suffered from depression throughout his life and that this escalated to suicidal thinking when he couldn’t pay for his infant daughter’s enormous medical bills. This triggered embarrassment, self-directed anger, and feelings of failure. Filled with urgency to escape his overwhelming pain, he got directions to the bridge and climbed over the railing. He was stopped by an empathetic police officer, Kevin Briggs, who spoke with him for an hour and a half on the ledge before he decided to climb back to safety. Berthia’s life was saved, but his struggles continued for years. In a piece for the Guardian, he wrote, “Reporters are always after the happily-ever-after ending.” This coverage stands out because it includes his backstory and the moment-to-moment details of Berthia’s path toward, and ultimately away, from suicide.

Suicide is the result of a culmination of factors pushing people into excruciating states where death is viewed as relief. Suicidologists acknowledge that diverse pathways lead to suicidal desire and seek to identify commonalities among people in acutely risky states. For example, Berthia had pre-existing vulnerabilities related to growing up with some family conflict and in a neighborhood where he was pressured to hide his depression. Then, compounding the uniquely jarring worry of having a child in compromised health, Berthia also blamed himself for not being able to foot medical bills to the tune of a quarter of a million dollars. This propelled him to the Golden Gate Bridge with the thought, “All I gotta do is lean back and everything is done. I’m free of all this pain.”

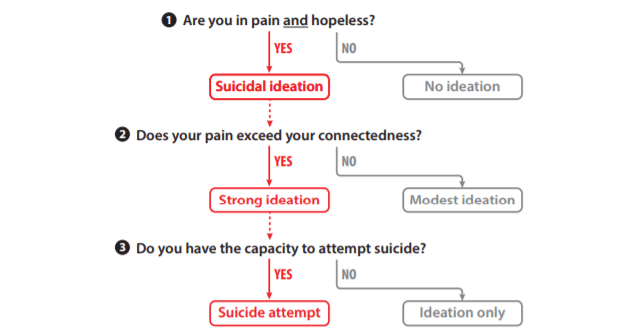

Between StoryCorps and the Guardian article, we get a sense of several contributing factors and potential intervention points that are generalizable beyond Berthia’s individual situation. For example, there seems to be a sustained cultural push against the belief that people should hide depression. And while the Affordable Care Act sought to partially address the dire state of affairs for many Americans facing medical costs, additional changes are desperately needed to overhaul a system that leaves people struggling to meet basic physical needs. A comprehensive suicide prevention initiative would address these and other empirically-linked risk factors (e.g., incarceration, homelessness, combat exposure, physical illness, mental illness, and discrimination). This long list of suicide risk factors can leave people feeling overwhelmed and unsure of how to help. Thankfully, Klonsky and May (2015) developed a scientific framework called the Three-Step Theory (3ST) that meaningfully organizes and prioritizes this information:

from Klonsky, May, & Saffer, 2016

Berthia’s experience appears to fit within the 3ST. The first step proposes that people desire suicide in the presence of pain and hopelessness about the future, “If someone’s day-to-day experience of living is characterized by pain, this individual is essentially being punished for living, which may decrease the desire to live and, in turn, initiate thoughts about suicide” (pp. 116-117). Within the 3ST, suicidal desire could be reduced by targeting both distal factors (e.g., eliminating environmental factors that increase the probability of emotional pain) and proximal factors (e.g., increasing hope and coping skills). People advance to the second step of increased suicidal intensity if their pain overpowers meaningful connections to life. In the moment Berthia was about to jump to his death, Briggs emphasized Berthia’s connection to his daughter and the suicidal intensity decreased, “My daughter, her first birthday was the next month. And you made me see that if nothing else, I need to live for her.” A society seeking to prevent suicide would foster these kinds of connections, at multiple levels, for as many people as possible. The 3ST makes the case, building on the interpersonal theory of suicide, that the survival instinct prevents most people from attempting suicide even if they desire it. The third step usefully identifies three facets of a capacity to override this survival instinct: dispositional (e.g., genetics related to pain sensitivity), acquired (e.g., experiences that result in decreased pain sensitivity and lowered fear of death), and practical (described as knowledge of and access to lethal means – e.g., in Berthia’s case, getting the directions to the bridge and not facing a suicide barrier once there). The practical aspect of capability for suicide has been the focus of initiatives to reduce access to lethal means in times of suicidal crises (e.g., through safe gun storage). Increasing safety at times of suicidal crisis can have long-lasting positive effects, as most suicide attempt survivors do not go on to die by suicide.

Suicide is complicated and that contributes to widespread misunderstanding. Science can guide us away from investing resources in domains that have unknown relationships with suicide and toward those that have demonstrably stronger ones. Research illuminates potent risk factors and makes our understanding of suicide more precise. Suicide prevention advocates have increased public awareness about a variety of different suicidal experiences and continue to fight for public policy aimed toward saving lives. Recently, there have been excellent examples of compassionate, realistic media coverage and fictional depictions of suicidal behavior. Altogether, this suggests that the public has the will to prioritize suicide as a public health problem. Scientific frameworks like the 3ST can steer us in productive, solution-focused directions.

—

Suicide prevention information resources are available here, and here’s a summary of intervention research.

You can hear more of Kevin Berthia’s story here:

You can hear Kevin Briggs speak about Berthia’s story here.

Pingback: Suicidal Behavior, Science, & Mixed Martial Arts with Dr. David Klonsky | Jedi Counsel

Pingback: Ask Me Anything about Suicide | Kathryn H. Gordon, Ph.D.

Pingback: The Suicidal Thoughts Workbook is Available Now! | Kathryn H. Gordon, Ph.D.